The Russian revolutions of 1917 were among the most consequential events of the 20th century. One-hundred years ago on November 7, a radical Marxist party came to power in Russia promising to establish socialism through the rule of workers’ and peasants’ councils known as soviets. Yet within one year after the soviet government’s birth, the new regime had become a one-party state with neither freedom nor democracy for Russia’s toiling classes.

What happened?

A one-party state rapidly emerged not by design but by default due to a series of decisions by the Bolsheviks destroying the embryonic elements of a democratic republic as well as those of soviet democracy. Far from being responses to the civil war and Allied intervention of 1918-1921, these decisions were made before the outbreak of civil war and remained unchanged after the war’s end in 1921.

Aborting the Democratic Republic

As democratic socialists, Marx and Engels held that democratic institutions, practices, and freedoms are indispensable prerequisites for both the establishment and maintenance of socialism – that is, the political rule of the working class, or more ominously, the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Consistent with this view, Engels wrote that “the working class can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic” and that a democratic republic “is even the specific form for the dictatorship of the proletariat.” Up until 1917, all Marxists around the world agreed with Engels, including both the Menshevik and Bolshevik factions of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP).

The Bolsheviks’ strategy for revolution was built around the goal of establishing a democratic republic. As Lenin put it, “Whoever wants to reach socialism by a different road, other than that of political democracy, will inevitably arrive at conclusions that are absurd and reactionary both in the economic and the political sense.” He wrote dozens of articles across decades urging workers and peasants – the vast majority of the Russian people – to unite and form a temporary revolutionary government that would overthrow the Tsar, disband the autocracy’s apparatus of repression (army, police, secret police), eliminate vestiges of feudalism, and with those tasks completed, convene a Constituent Assembly elected on the basis of universal suffrage. This Constituent Assembly would establish a republic with a democratic constitution as Russia’s permanent government, marking the final act of the democratic revolution – and for Marxists, the opening act of the socialist revolution.

Summoning a Constituent Assembly to inaugurate a democratic republic was perhaps the one issue that the Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SR), Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadet), and the Provisional Government all agreed on in 1917. As historian Lars Lih notes:

“Long before 1917, Russian revolutionaries had traditionally called for a Constituent Assembly that would establish a new post-revolutionary political order. An elected Constituent Assembly would be the cleanest and most radical break with the existing tsarist system—a guarantee that the tsarist government itself could not influence the outlines of the future. Even though the February revolution disposed of the tsar and his government more sweepingly than expected, a Constituent Assembly remained an axiomatic goal in 1917, one accepted by the entire political spectrum.”

When the Provisional Government delayed the convocation of a Constituent Assembly throughout 1917, the Bolsheviks argued that the Provisional Government could not be trusted to do the job and proposed that a soviet government convene the assembly instead. According to the Bolsheviks, “all power to the soviets” was the only sure way to get all power to the Constituent Assembly. That scenario is exactly what the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets sanctioned on November 8, 1917 when it passed this resolution establishing the soviet government:

“The All-Russia Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, and Peasants’ Deputies resolves: To establish a provisional workers’ and peasants’ government, to be known as the Council of People’s Commissars, to govern the country until the Constituent Assembly is convened. … Governmental authority is vested in a collegium of the chairmen of those commissions, i.e., the Council of People’s Commissars. Control over the activities of the People’s Commissars with the right to replace them is vested in the All-Russia Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and its Central Executive Committee.”

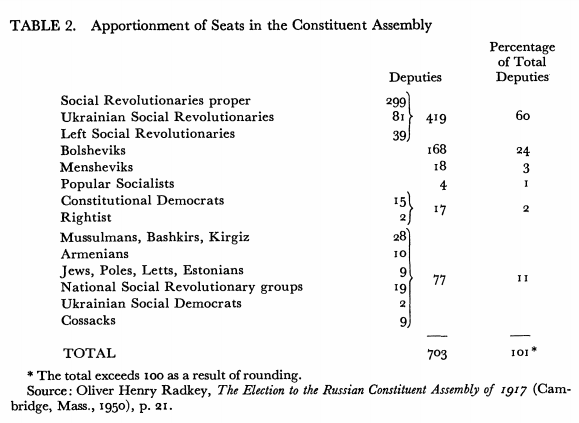

Constituent Assembly elections were held throughout Russia on November 25 with the following results:

The Bolsheviks were soundly defeated by the SRs. As soon as the elections returns came in, the Bolsheviks – with Lenin leading the charge – began preparing to liquidate the Constituent Assembly in defiance of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets’ explicit mandate. Lenin justified the soviet government’s usurpation of the Constituent Assembly’s role as the final arbiter of the post-Tsarist political order on the following grounds:

- The party that won the Constituent Assembly election, the SRs, split into two parties (SRs and Left SRs) after ballots had been printed and distributed to voters but before the election was held.

- Soviets are a “higher form” of democracy than the Constituent Assembly.

The first statement is true. However, inaccurate electoral lists is an argument for re-running the elections with updated lists and not forcibly dispersing and abolishing the Constituent Assembly altogether as the Bolsheviks did in January 1918.

The second statement is an assertion unsupported by facts given how both systems worked in practice. For starters, over 40 million people voted in the Constituent Assembly elections while the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets only claimed to represent the will of 20 million electors. Secondly, the 1918 soviet constitution systematically discriminated against 85% of the Russian population, the peasants, by giving rural soviets just 1 delegate to national soviet congresses of soviets per 125,000 inhabitants compared to 1 delegate accorded to urban soviets for every 25,000 voters.

How can a system that practices de jure discrimination against 85% of the population with 20 million participants be a “higher form of democracy” than a rival system without such discrimination in which twice as many people participate?

Strangling the Soviets

Sadly, the soviets that the Bolsheviks touted as a “higher form of democracy” fared no better than the Constituent Assembly under Bolshevik rule.

When the Bolsheviks lost majorities to the Mensheviks and SRs in all 19 cities where soviet elections were held in spring of 1918 (soviet governance existed in a total of 30 cities in European Russia at this time), instead of peacefully transferring power to these parties the Bolsheviks disbanded all 19 soviets by force.

This was not the exception but the rule. There is not one known case of the Bolsheviks respecting the results of free and fair soviet elections that they lost after their November 1917 insurrection supposedly put “all power” into the hands of the soviets.

In Petrograd – the heart of the 1917 revolutions – the Bolsheviks responded to their growing unpopularity in early 1918 by revoking the electors’ right to immediately recall their delegates to the city soviet. After resisting calls for new elections for almost six months (the soviet’s term in office expired in spring of 1918), the Bolsheviks scheduled new elections for June 1918. However, they altered the soviet’s composition to minimize representation from factories (where workers voted directly for representatives) and maximize representation from Bolshevik-controlled bureaucracies like the army and trade unions (whose representatives were chosen not by direct elections but by the leadership bodies of these organizations). This was the delegate composition of the Petrograd soviet in fall 1917:

| Workplaces | 259 |

| Military Units | 440 |

| Trade Unions | 60 |

| Railways | 17 |

| Political Parties | 12 |

| District Soviets | 3 |

This was the delegate composition of the Petrograd soviet in June of 1918:

| Workplaces | 260 |

| Military Units | 68 |

| Trade Unions | 144 |

| Railways | 72 |

| Political Parties | 0 |

| District Soviets | 46 |

| Workers’ Conferences | 88 |

It is important to note that by June 1918, delegates from military units were not elected but appointed from above by Bolshevik authorities. (The Bolsheviks restored the traditional top-down bourgeois officer corps system in spring of 1918, effectively overturning the Petrograd Soviet’s infamous Order No. 1 in March 1917 democratizing military units and the chain of command.) Furthermore, proportional representation in the Petrograd soviet was also abolished and replaced by a winner-take-all system, eliminating one-third of the 1st District Soviet’s delegates who were Mensheviks or SRs. Of the 260 workplace delegates directly elected by workers to the soviet in June 1918, 123 were Mensheviks and SRs, 82 were Bolsheviks, 15 were Left SRs, and 10 were non-party.

The Bolsheviks also expanded the size of the soviet even as the size of the city’s working class shrank drastically. In 1918, the Petrograd soviet consisted of 678 delegates; in 1920, it consisted of 2,000 delegates (more than 50% of them from military and police units). By contrast, the city’s proletariat shrank from 274,000 in 1917 to 140,000 in 1918 and 102,400 by 1920. ‘Representation’ of trade unions and railway organizations doubled in the Petrograd soviet and a brand new category of delegates – “workers’ conferences” – appeared out of thin air while the city’s working class was cut in half between fall of 1917 and summer of 1918.

The “dictatorship of the proletariat” was drowned in the Petrograd soviet by a sea of bogus ‘representatives’ i.e. Bolshevik bureaucrats. Of the city’s 22,000 Communist Party members in 1920, 2,000 of them had seats in the soviet and so a party encompassing only 3% of the city population enjoyed a 90% majority in the city’s legislature.

Bolshevik respect for soviet democracy was no better on the national level.

The Bolshevik-controlled Central Executive Committee (CEC) – the soviet government’s national legislature – expelled its Menshevik and SR members a few weeks before the Fifth All-Russian Congress of Soviets in July 1917, an illegal move under soviet law since only a congress of soviets had the authority to determine the CEC’s political complexion and these CEC members had been duly elected by the Fourth All-Russian Congress of Soviets. Unfortunately, the Bolsheviks had no respect for soviet law; as Lenin wrote in 1918, “dictatorship is rule based directly upon force and unrestricted by any laws.”

When it became evident that the Left SRs would either have parity with or even outnumber the Bolshevik delegates at the Fifth All-Russian Congress of Soviets since they swept village soviet elections in rural areas, the Bolsheviks stacked the congress with roughly 400 bogus delegates. Once the Left SRs finally understood that it would be impossible to overturn the Brest-Litovsk Treaty by legal, peaceful, constitutional means within the soviet system by obtaining a majority at a national soviet congress since the Bolsheviks would resort to fraud and foil them, their central committee hatched a conspiracy to kill the German ambassador in a desperate bid to rekindle hostilities on the eastern front, thereby killing the treaty. In response, not only did the Bolsheviks arrest the plotters but the entire Left SR party was outlawed on the pre-text that the party tried to overthrow the soviet government. In fact, Left SR party members were completely unaware of their leadership’s conspiracy to kill the ambassador, made no preparations for an armed uprising, and viewed soviet rule as the only legitimate form of government.

Soviet Russia had become a one-party autocracy less than one year after the soviet government formed primarily due to Bolshevik hostility to democratic institutions, practices, and freedoms once they seized power in November 1917. “All power to the soviets” was never put into practice. After the Provisional Government was overthrown, power was in the hands not of soviets but of Bolshevik commissars who alone controlled “special bodies of armed men” – the Cheka and military units – that within a few years killed tens of thousands of striking workers and rebellious peasants who came to resist the new autocracy ruling in their names.

Conclusion

Once in power, Lenin and the Bolsheviks immediately abandoned Marx’s and Engels’ vision of democratic socialism, specifically:

- Limits on Executive Power (human and civil rights; rule of law; due process; separation of powers; independent judiciary).

- Popular Sovereignty (universal suffrage; free and fair elections; peaceful transfer of power).

- Individual Liberty (freedom of speech, the press, assembly, and association).

In jettisoning the teachings of Marx and Engels, the Bolsheviks also abandoned the political core of their own party’s program:

“The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party takes as its most immediate political task the overthrow of the Tsarist autocracy and its replacement by a democratic republic, the constitution of which would ensure:

- Sovereignty of the people—that is, concentration of supreme state power wholly in the hands of a legislative assembly consisting of representatives of the people and forming a single chamber.

- Universal, equal and direct suffrage, in elections both to the legislative assembly and to all local organs of self-government, for all citizens and citizenesses who have attained the age of 20; secret ballot at elections; the right of every voter to be elected to any representative body; biennial parliaments; payment of the people’s representatives.

- Extensive local self-government; regional self-government for all localities which are distinguished by special conditions in respect of mode of life and make-up of the population.

- Inviolability of person and domicile.

- Unrestricted freedom of conscience, speech, publication and assembly, freedom to strike and freedom of association.

- Freedom to travel and to engage in any occupation.

- Abolition of social estates, and complete equality of rights for all citizens, regardless of sex, religion, race and nationality.

- Right of the population to receive education in their native language, to be ensured by provision of the schools needed for this purpose, at the expense of the state and the organs of self-government; the right of every citizen to express himself at meetings in his own language; use of the native language on an equal basis with the state language in all local, public and state institutions.

- Right of self-determination for all nations included within the bounds of the state.

- Right of any person to prosecute any official before a jury, through the usual channels.

- Judges to be elected by the people.

- Replacement of the standing army by universal arming of the people.

- Separation of the church from the state and of the school from the church.

- Free and compulsory general and vocational education for all children, of both sexes, up to the age of 16; poor children to be supplied with meals, clothing and textbooks at state expense.”

The 100-year anniversary of the October Revolution should not to be a time for socialists to celebrate Lenin or Trotsky but to memorialize the working people whose hopes and aspirations they exploited and betrayed. Their voices have been largely forgotten, erased from the historical record since the victors write history and the victorious Bolsheviks could never account for proletarian uprisings and general strikes under “the dictatorship of the proletariat.” Forgotten are the words of a resolution passed by a mass meeting of 10,000 workers defending the democratic socialist ideals of 1917 from Bolshevik perfidy on the eve of a 1919 general strike in Petrograd:

“We, the workmen of the Putilov works and the wharf, declare before the laboring classes of Russia and the world, that the Bolshevik government has betrayed the high ideals of the October revolution, and thus betrayed and deceived the workmen and peasants of Russia; that the Bolshevik government, acting in our name, is not the authority of the proletariat and peasantry, but the authority of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, self-governing with the aid of the Extraordinary Commissions [Chekas], Communists and police.

“We protest against the compulsion of workmen to remain at factories and works, and attempts to deprive them of all elementary rights: freedom of the press, speech, meetings, and inviolability of person.

“We demand:

- Immediate transfer of authority to freely elected Workers’ and Peasants’ soviets.

- Immediate re-establishment of freedom of elections at factories and plants, barracks, ships, railways, everywhere.

- Transfer of entire management to the released workers of the trade unions.

- Transfer of food supply to workers’ and peasants’ cooperative societies.

- General arming of workers and peasants.

- Immediate release of members of the original revolutionary peasants’ party of Left Socialist Revolutionaries.

- Immediate release of Maria Spiridonova. [Left SR leader]”

The Bolsheviks crushed this strike and criminalized possession of the above resolution. Ultimately, repression could not save their wretched regime any more than it could save the Tsar’s. Both were rightly consigned to the dustbin of history by democratic revolutions.

great article.

LikeLike

Thank you! 😀

LikeLike

Comrade, I don’t think it’s appropriate to post this kind of article on the centenary of the October Revolution. Nobody finds what happened starting in March 1918 as repugnant as I do (as I’ve posted on this myself previously), but if even the “post-capitalist” social-democrat Paul Mason can “reject Bolshevism” while celebrating what happened a century ago, you should, too!

LikeLike

Within three weeks of the October revolution, the Bolsheviks closed more socialist newspapers than the Tsar did in the previous three decades and arrested fellow socialists. I fail to see why that’s worth celebrating.

LikeLike

Great article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

More information on how the Bolsheviks began repressing workers, peasants, and socialists as soon as they took power: https://medium.com/@pplswar/dsas-jason-schulman-dead-wrong-on-lenin-the-bolsheviks-and-the-october-revolution-9ff02b1f5247

LikeLike

Lets not forget how this trash murdered the Orthodox Christians and burnt their Churches.

Lets not forget the murderers Bronstein and Kaganovich.

The Christian Cossacks could never be defeated by the Commie Bolsheviks and are now a force again in Christian Russia.

LikeLike

You’re right. This post is not meant to be a definitive or exhaustive history of Bolshevik atrocities. The Bolsheviks arguably committed genocide against the Cossacks with their whole extermination campaigns targeting civilians including women and children.

LikeLike

Democracy — “democratic institutions, practices, and freedoms” — is not worth worshipping, for it may as well be a dictatorship of bourgeoisie.

LikeLike

So you’re saying Marx was completely wrong.

Good luck with that.

LikeLike